by Ernesto Oroza | designer & artist

Images by Ernesto Oroza

INTRODUCTION

Cuba is a Caribbean country ruled since 1959 by a self-declared communist regime that came to power through armed struggle. The expropriation and nationalization measures implemented by the new government in the early years of the revolution resulted in a severe conflict of interest with the United States. As a result, John F. Kennedy declared in 1962 a commercial and financial embargo on the island, which is still in force (2015). Informational isolation and inaccessibility to basic resources and goods have characterized daily life in Cuba for over 50 years. For decades the government itself has practiced audiovisual piracy to supply materials to the official television channels. In the universities of the country, hundreds of books and international periodical publications have been pirated to meet the educational and informational needs of students.

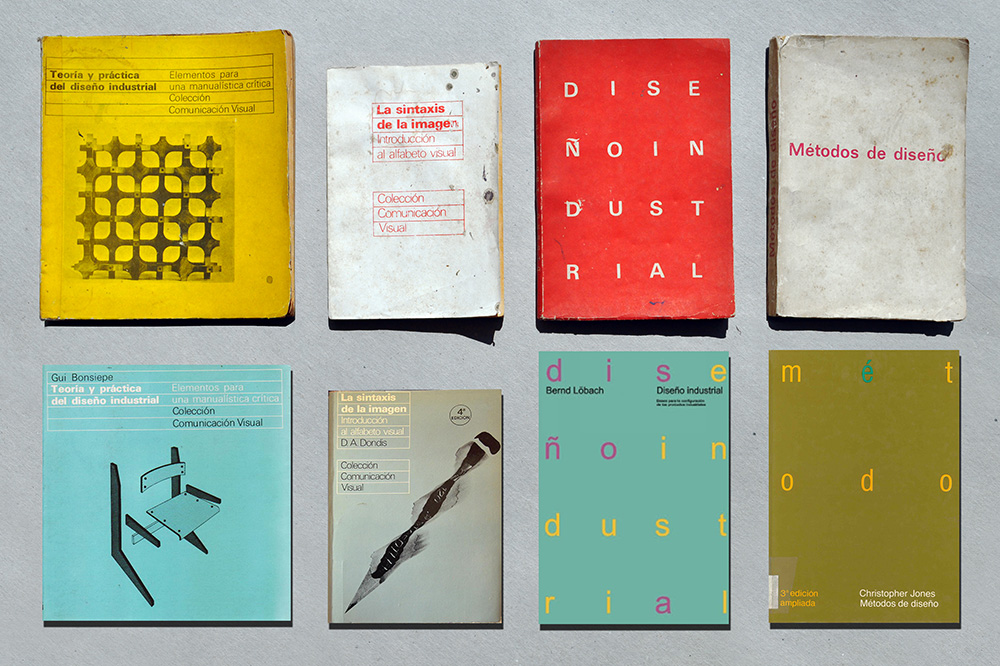

Books distributed to the students by the Institute of

Design in Havana (originals and pirate copies)

ORIGINS OF EL PAQUETE SEMANAL

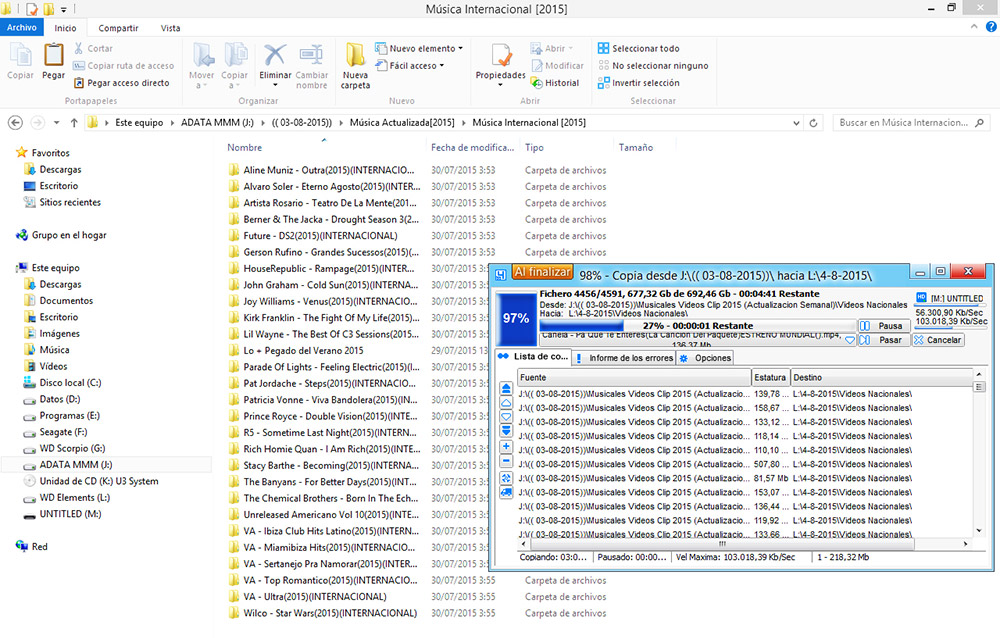

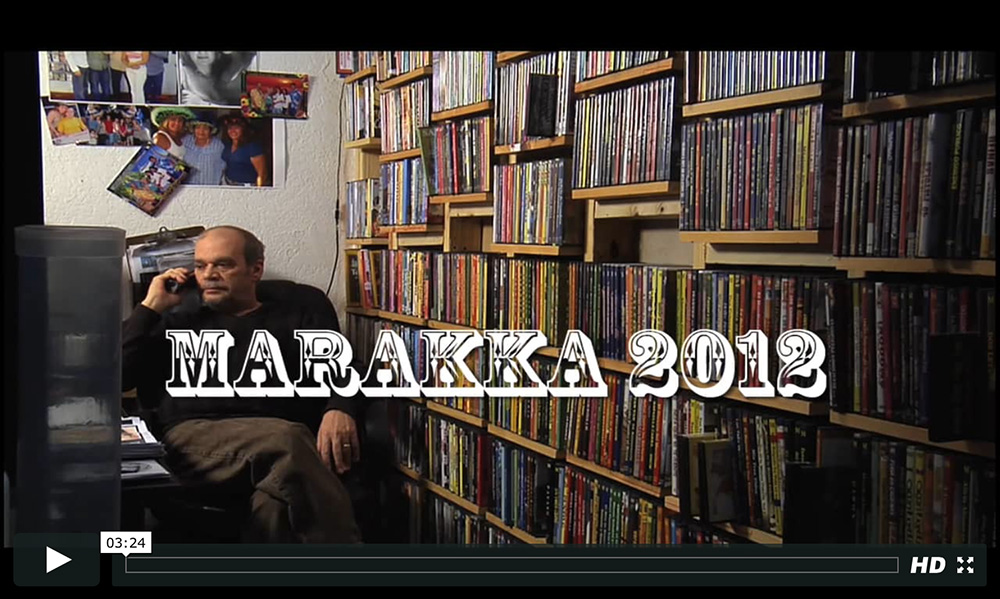

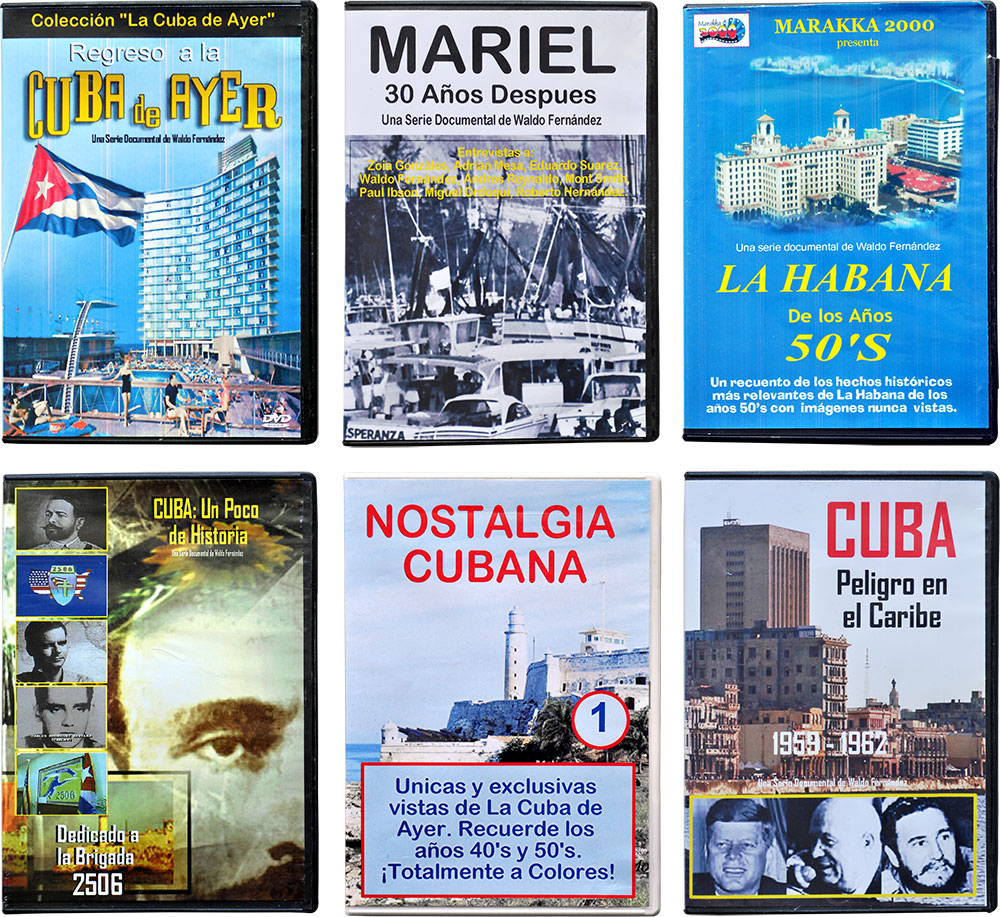

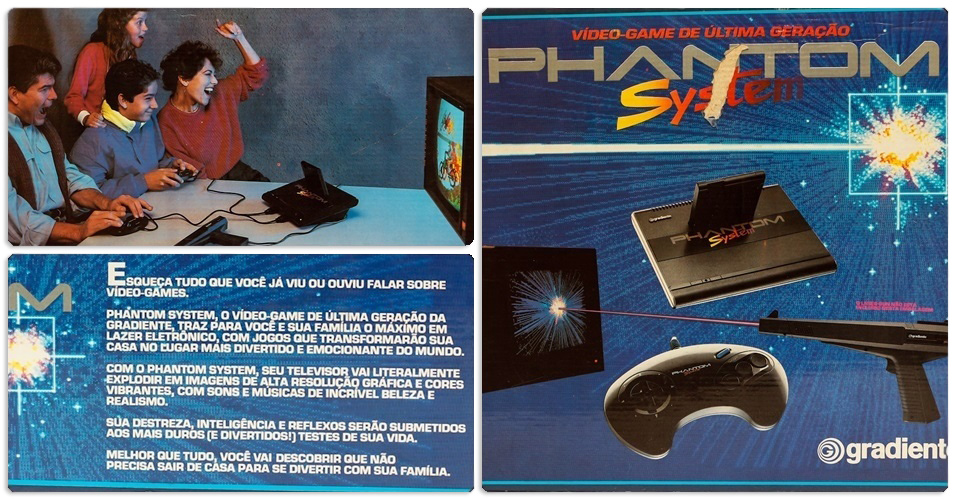

It all started maybe 10 or 15 years ago. I remember that my nephew was the first one in the family doing it. He had a little USB hard drive, and one day he got a large quantity of films from a neighbor – things such as National Geographic nature documentaries, music, action films, and video clips. Computers were rare in Cuba at the time. You could find maybe one computer on each block. Some people who had computers started collecting and selling kits of digital contents; it became a way to earn money. You could buy one terabyte of contents, connect the hard drive directly to a television, and watch it without any computer. You just needed to bring your own hard drive to the seller and transfer the files at his place. You could even customize the package by asking for a part of it only (to save money) or for more specific contents (only kung fu movies, TV shows, games, music, etc.). Today, El Paquete could include series, films, soap operas (people love Korean soap operas right now), documentaries, music, video clips, reality shows, graphic humor, comics and cartoons, software, apps, antivirus software, language courses, magazines in PDF format, advertising, and an offline version of Revolico, among other materials. The contents for each issue of El Paquete are usually collected from online sources. Some foreigners and people connected to foreign companies, embassies, or consulates have satellite antennas in their houses, and some people have illegal satellite antennas too. Maybe the creators of El Paquete are people working for the government in official institutions with large digital bandwidth that allows downloading long videos and music compilations. The fact is that somebody is recording the materials, transferring them onto hard drives, and preparing a new compilation every week (El Paquete Semanal, “The Weekly Package”). There’s also extensive clandestine traffic of digital devices between Cuba and Miami. This includes USB flash drives and hard drives, but some cultural content for El Paquete is also transported this way. The cost of a full El Paquete is about 1 CUC (24-25 Cuban pesos), so in terms of local income, it’s expensive given that the average monthly salary is between 15 and 20 CUC a month.

But in Cuba quite often multiple generations live in the same house: grandparents, parents, and children. So the expense of a single copy of El Paquete is often shared among the extended family. For those who distribute the package, the cost, if acquired directly from the matrix, varies according to the day on which it was bought between 10.00 CUC and 3.00 CUC, Sunday being the most expensive. These dealers cross the city by bike and have dozens of clients who spend 10 CUC weekly. Now there is new street vendor license available named “Disk Seller and Buyer,” so many people are selling partial contents of El Paquete using DVDs and CDs, especially series, video clips, and international soap operas.

ANTI-PAQUETE

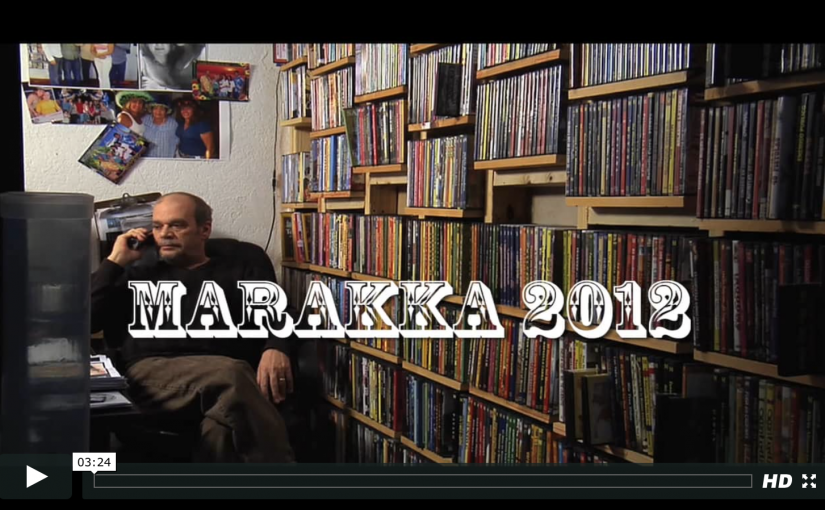

El Paquete became a big problem in Cuba because the government is particularly afraid of this mode of content distribution. According to the authorities, not only is it out of control and promotes contamination by American culture, its artistic/intellectual level is also quite low, as it’s full of American blockbusters and Mexican soap operas. The government claims that Cubans instead need educational material for young people, something that is good for the new generation, not films with sex or violence. Nevertheless, I remember that for many years every Saturday at 9 p.m. you could watch two or three pirated American movies on national television, blockbusters like Die Hard for example. People loved it, and it was common to say in a conversation that something was like “Saturday’s film,” meaning that it had sex and violence. But when the phenomena of El Paquete started, the real preoccupation of the government wasn’t the artistic quality of its content, but politics; they didn’t want it to be used for spreading information against the government. This USB package was spontaneous, unpredictable, and impossible to control. Of course it quickly became illegal; if you were caught selling it, you could go to prison or the government could confiscate your computer. But some other methods to stop El Paquete were also tested. One example was the creation of a direct rival: the authorities made their own Paquete named Maletín or Mochila, which means a “bag” or “backpack” in English. Inside, instead of US blockbusters, you could find classical movies and music and educational materials. Actually, people found it very boring and nobody liked it, so this anti-Paquete system was a total failure. And of course it was just as pirated as the clandestine one: the government did not pay for its contents either; it was all “stolen.”

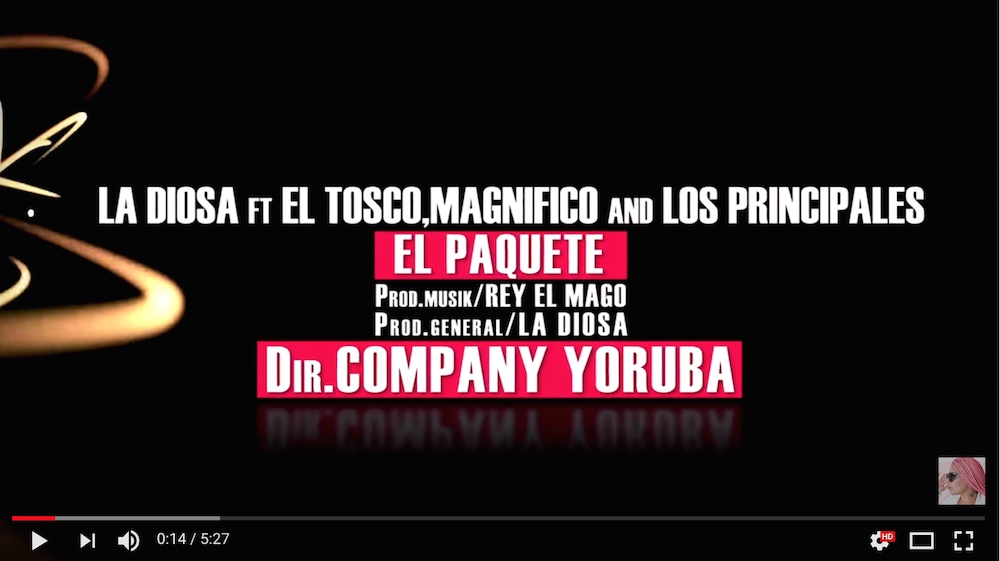

Another attempt involved the creation of anti-Paquete propaganda: I remember a very dramatic report on the TV news about computer virus attacks all over the world that showed USB and El Paquete iconography and claimed that hackers could use these viruses to steal your information or destroy your computer. Another faction of the government, mostly intellectuals, are proposing to contaminate El Paquete with cultural contents, I guess Godard, Glauber Rocha, and Bergman, but for many this will be an extension of the indoctrination that Cubans have endured for more than 50 years through information, education, and cultural systems. Anyway, before the government pro-posed it, some cultural producers such as reggaeton singers, filmmakers, designers and editors, among others, began using El Paquete for the distribution of their works and activities. There are even some original materials created specifically for this distribution channel. There are many local bands which created video clips especially for El Paquete: national television does not promote them and YouTube is banned, so they use El Paquete for distribution and promotion (e.g., La Diosa “El Paquete”, with a strong message: “If you’re not inside the Paquete, you don’t exist!”).

WEB IN A BOX

Revolico is the Cuban version of Craigslist, a website where people can directly publish small ads to sell or exchange different kinds of goods and services: cars, jobs, clothes, animals, electronics, etc. The problem is that people need to have access to the Internet to use it, and in Cuba it’s mostly impossible. People in Cuba love and need Revolico because it’s the only way to exchange materials, information, and goods. So Revolico went inside El Paquete as a list of small ads. In a recent interview I conducted with the creators of Revolico, Hiram (a co-founder) explained that they are now working on a new offline version of this platform that will be ready soon to take advantage of the El Paquete distribution system.

SNET

Today, in Cuba more and more people have computers and other electronic devices such as tablets and smartphones, but home Internet and Wi-Fi access remains forbidden unless you have special permission from the Ministry of Communications (recently the government opened 35 points with public Wi-Fi around the country with a cost of 2 CUC per hour, and service is limited). As a consequence, there is a new phenomenon called SNet (Street Net), a sort of clandestine network. At the beginning young people started to use telephone cables to connect computers in the neighborhood in order to play games in a network. Later, they found a way to connect the computers using Wi-Fi. Today, this network consists of about 10,000 computers. The police also access the system to monitor the flux of information. The government warns that if you share counter-revolutionary material or other forbidden content, it will break the whole SNet system. Despite this, SNet has become one of the main avenues for playing collective games and information distribution. Besides SNet, there is also a governmental Internet, a very slow and monitored intranet. Every e-mail that is written in Cuba is tracked by the political police. There are many systems to monitor key words. Some government employees or institutions have a faster and more direct Internet connection, with access to Yahoo, Hotmail, etc., but it’s still impossible to access other big international platforms such as YouTube and Google Maps. Recently, I collaborated with some SNet administrators to test the possibilities of the net. We designed a small program and inserted it to produce a collective poem based in the exquisite corpse method. We got a poem of 3,000 words in just a week, meaning that many users of SNet were involved.

thepiratebook.net - 2015