Introduction by Marie Lechner,

journalist & researcher

PREAMBLE

The Pirate Book by Nicolas Maigret and Maria Roszkowska is both a visual essay and anthology, written in the wake of the Jolly Roger’s infamous skull and crossbones and compiled during its journey across the four corners of the world. In this book, the authors invite us to shift our perspective on piracy itself. This polyphonic work constitutes an attempt at probing the ambiguity inherent to piracy and at re-evaluating the issues related to it. The Pirate Book, moreover, signifies a departure from the one-sided approach adopted by the cultural industries which consists in designating the figure of the pirate as public enemy number 1. Intellectual property was, in fact, called into existence in order to ward off those that Cicero, in his time, called “the common enemy of all.” At the outset, intellectual property’s purpose was to protect authorship and promote innovation; however, it eventually hindered technological progress and encouraged cultural products, which had hitherto belonged to the public domain, to be snatched away from it.

This book arises from a previous installation-performance by Nicolas Maigret, The Pirate Cinema, where the artist visualizes the covert exchange of films in real time at dazzling speed under the cover of worldwide peer-to-peer networks. The advent of the Internet and its users’ unbridled file sharing capability on peer-to-peer networks has resulted in an unprecedented proliferation of illegal downloading since the 1990s. This situation also very quickly led to online piracy being singled out as the primary cause of the crises affecting the music and film industries, whereas certain other voices deemed piracy to be the scapegoat of the cultural sector that had not managed to properly negotiate the transformations it underwent following the onset of the digital era.

PIRACY AS EXPERIMENTATION

The term piracy more generally designated the unauthorized usage or reproduction of copyright or patent-protected material. This is almost a far cry from the word’s original etymology. “The word piracy derives from a distant Indo-European root meaning a trial or attempt, or (presumably by extension) an experience or experiment,” writes Adrian Johns in Piracy: The Intellectual Property Wars from Gutenberg to Gates in which he highlights the fact that “It is an irony of history that in the distant past it meant something so close to the creativity to which it is now reckoned antithetical.” The Pirate Book endeavours to gain an insight into this very creativity. By calling on the contributions of artists, researchers, militants and bootleggers, this book brings together a large variety of anecdotes and accounts of local and specific experiences from Brazil, Cuba, Mexico, China, India, and Mali, all of which foreground the lived, personal and perceived aspects of such experiences. Despite the legal arsenal that has unfurled as well as the economic and political restrictions in place, The Pirate Book provides an illustration of the vitality of pirate (or peer-ate) culture. A culture that arose from necessity rather than convenience. A culture that has devised ingenious strategies to circumvent the armoury in place in order to share, distribute, and appropriate cultural content and thereby corroborate Adrian Johns’ view that “piracy has been an engine of social, technological, and intellectual innovations as often as it has been their adversary.” The author of Piracy believes that “the history of piracy is the history of modernity.”

STEAL THIS BOOK

The concept of intellectual piracy is inherited from the English Revolution (1660 – 80) and, more specifically, from the book trade. The Pirate Book is, as its name suggests, a book. An e-book, to be precise; a format that at the time of publication is currently very popular due to the development of tablets and readers. The increase in illegally available content that is concomitant with the growth of the e-book sector has raised fears that this sector will be doomed to the same fate as the film and music industries. By way of example, Michel Houellebecq’s latest blockbuster novel Soumission was pirated two weeks prior to its release. This marked the first incident of its kind in France. The arrival of the first printing press in England in the 1470s brought about the reinforcement of intellectual property rights regarding books. More specifically, this was achieved by way of monopolies granted by the Crown to the guild of printers and booksellers that was in charge of regulating and punishing those who illegally reprinted books. In 1710, the London guild obtained the Statute of Anne, the first law to recognize author’s rights, but also to limit copyright (which until then had been unlimited under the guild) to 14 years, with a possible extension if the author was still alive. The Pirate Book places side by side the Statute of Anne with the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), the American copyright law of 1998 that aimed at curbing the new threats posed by the generalisation of the Internet. The Pirate Book revisits some of the milestones of this history of piracy, by juxtaposing and comparing an image from the past with its contemporary counterpart. Such is the case with the musical score of Stephen Adams’ Victorian ballad, The Holy City, that became the most “pirated” song of its time towards the end of the 19th century and is presented opposite the album, Nothing Was the Same, by the Canadian rapper Drake that became the most pirated album of the 21st century (it was illegally downloaded more than ten millions times). Despite being the nation that ostensibly spearheads the war on piracy, the United States was at its inception a “pirate nation” given its refusal to observe the rights of foreign authors. In the absence of international copyright treaties, the first American governments actively encouraged the piracy of the classics of British literature in order to promote literacy. The grievances of authors such as Charles Dickens fell upon deaf ears, that is until American literature itself came into its own and authors such as Mark Twain convinced the government to reinforce copyright legislation.

PIRACY, ACCESS, AND PRODUCTION INFRASTRUCTURE

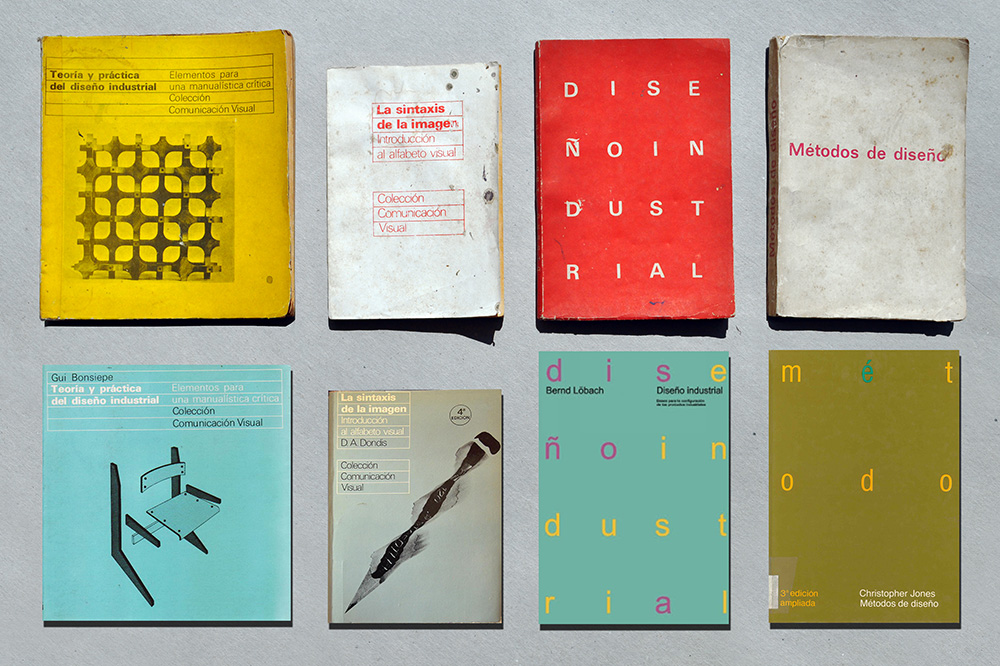

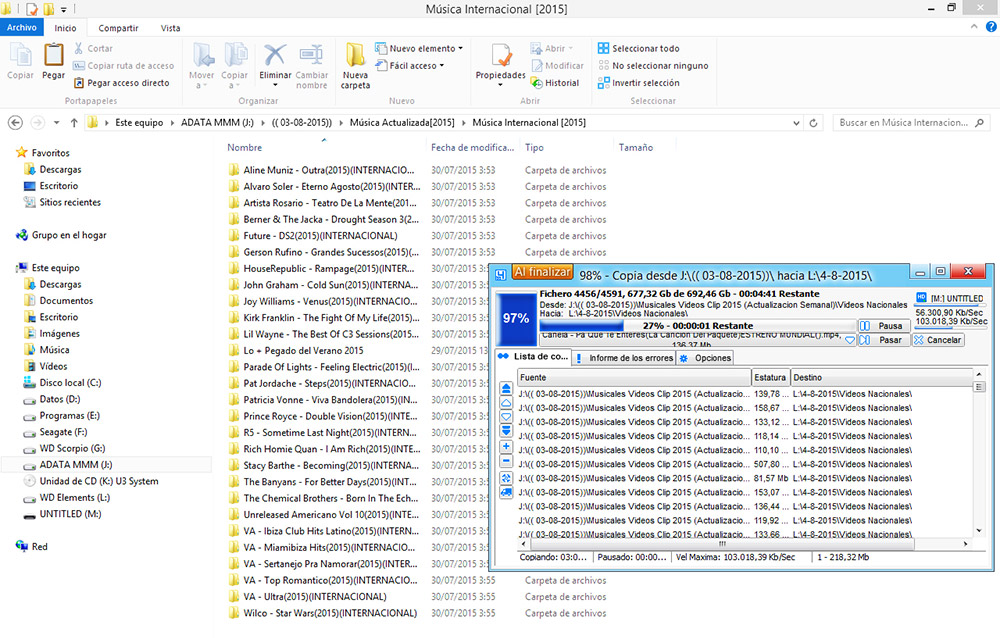

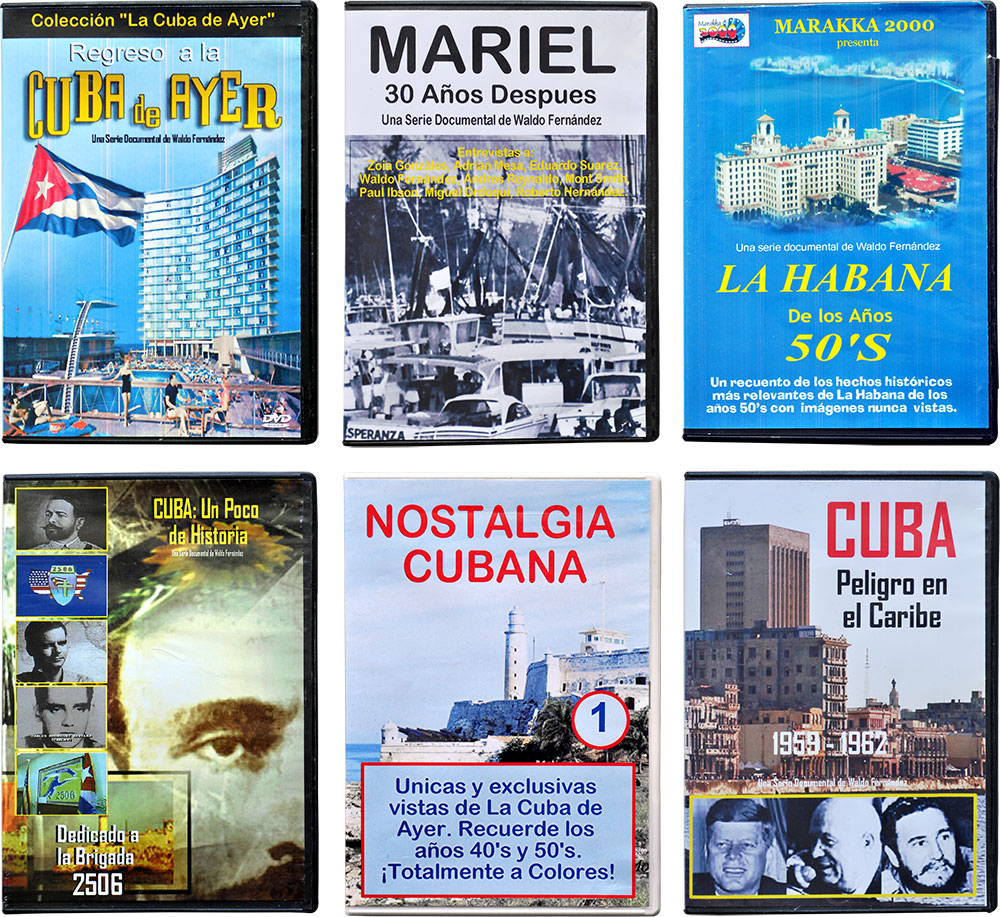

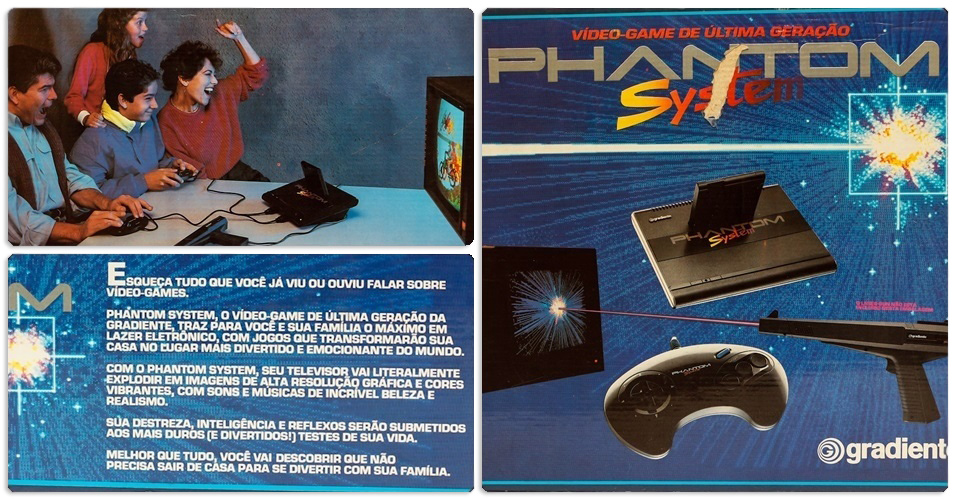

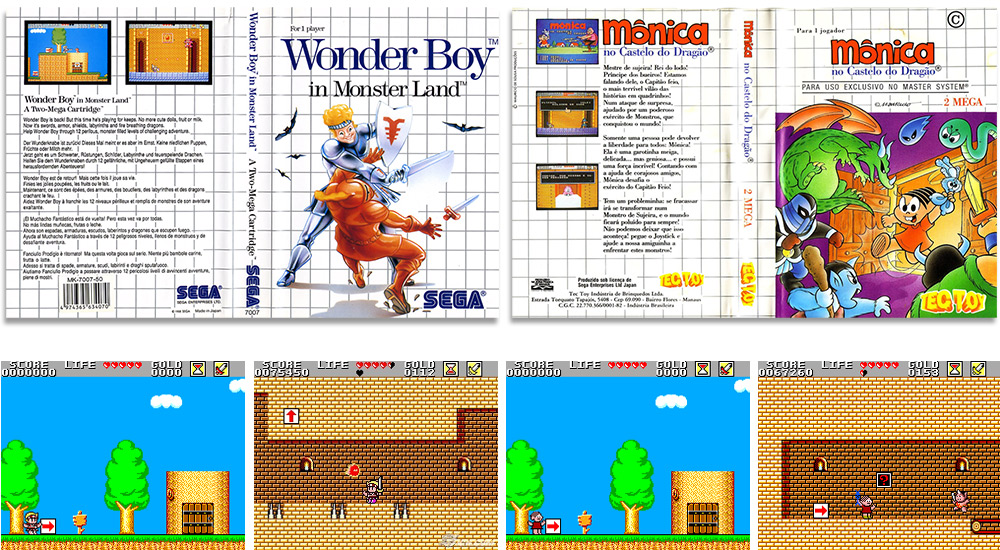

The article “Piracy, Creativity and Infrastructure: Rethinking Access to Culture,” in which the Indian legal expert Lawrence Liang situates the issue of the piracy of cultural artefacts in emerging economies, also rejects the narrow view of piracy as a solely illicit activity and goes on to depict it as an infrastructure providing access to culture. The abundantly illustrated stories brought together in The Pirate Book all inform this notion by inviting the reader to shift perspective. As described by the researcher and legal expert Pedro Mizukami, the emergence of bootlegged video rentals and consoles in Brazil was directly linked to the country’s industrial policies of the 1980s which aimed at closing the Brazilian market to imports in order to stimulate the growth of local productions, some of which were exorbitantly priced. Cuba’s isolation by the US embargo since 1962 and its ensuing inability to procure basic resources provided a fertile ground for audio-visual piracy on the part, among others, of the government itself in order to supply its official television channels with content as well as to provide its universities with books, as highlighted by the designer and artist Ernesto Oroza. Despite being poorly equipped, Cubans are able to get their hands on the latest action films, TV series, or music video thanks to a weekly, underground compilation of digital content called El Paquete Semanal that is downloaded by the rare Cubans who own a computer (around 5% of the population has Internet access) and sold on a hard drive that can be plugged directly into a TV. The downloaders of Fankélé Diarra Street in Bamako, who are the subject of Michaël Zumstein’s photographs, employ the same system of streetwise savvy. They exchange the latest music releases on their cell phones via Bluetooth, thus forming an ad hoc “African iTunes” where you can pick up the files offline in the street. This small-timer operation is also a must for local musicians to raise their profile.

FROM COPY TO CREATION, THE SHANZHAI CULTURE

Liang claims that piracy makes cultural products otherwise inaccessible to most of the population available to the greatest number of users, but also offers the possibility of an “infrastructure for cultural production.” The case of the parallel film industry based in Malegaon is literally a textbook case. The Indian researcher Ishita Tiwary tackles the case study of this small backwater of central India that has arisen thanks to an infrastructure created by media piracy and the proliferation of video rentals. Using the same mode of operation as Nollywood in Nigeria, people seize the opportunities provided by cheap technology in order to make “remakes of Bollywood successes” by adapting the content to the realities of the target audience’s lives. Servile replication, one of the objections often levelled at piracy, then gives way to “creative transformation” according to Lawrence Liang’s own terms. Another noteworthy example is the Chinese village of Dafen that is notorious for its painters who specialize in producing copies of well-known paintings. Dafen has now become home to a market for Chinese artists selling original works, which just goes to show how “A quasi-industrial process of copying masters has led to the emergence of a local scene.” This same process is aptly described by Clément Renaud, a researcher and artist, who took an interest in Shanzhai culture (literally meaning “mountain stronghold”), the flourishing counterfeiting economy of China, a country whose non-observance of copyright law is decried worldwide. “When you have no resources, no proper education system and no mentors at your disposal, then you just learn from your surroundings: you copy, you paste, you reproduce, you modify, you struggle – and you eventually improve,” resumes Clément Renaud by noting the rapid versatility and resourcefulness of these small-scale Chinese companies when faced with the demands of the global market. These “pirates [work] secretly (…) in remote factories, they have built a vast system for cooperation and competition. They shared plans, news, retro-engineering results and blueprints on instant messaging groups,” observes the researcher for whom this form of collaboration is reminiscent of open-source systems.

WAREZ CULTURE & FREEWARE

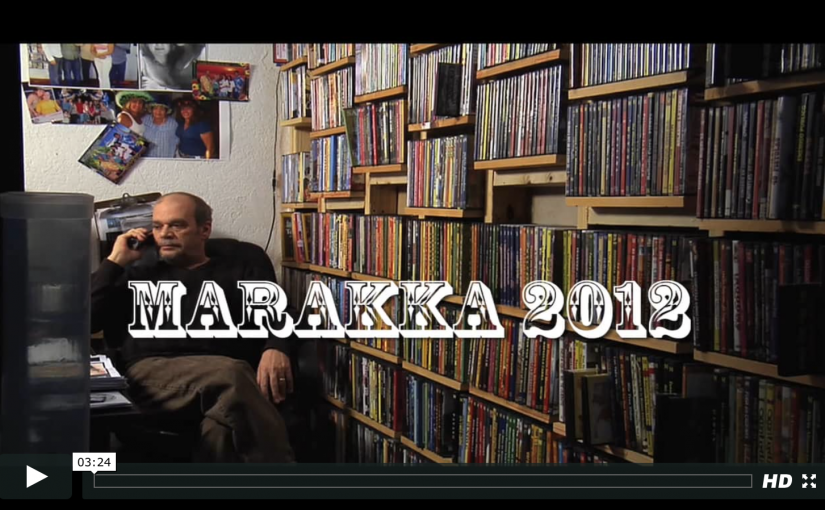

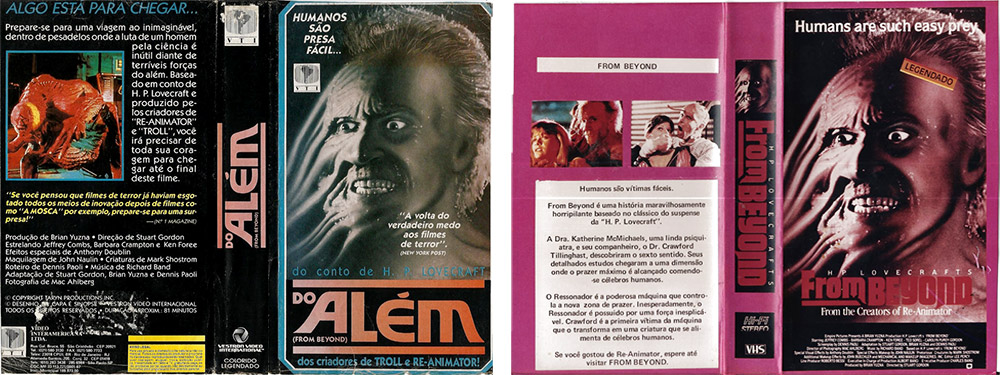

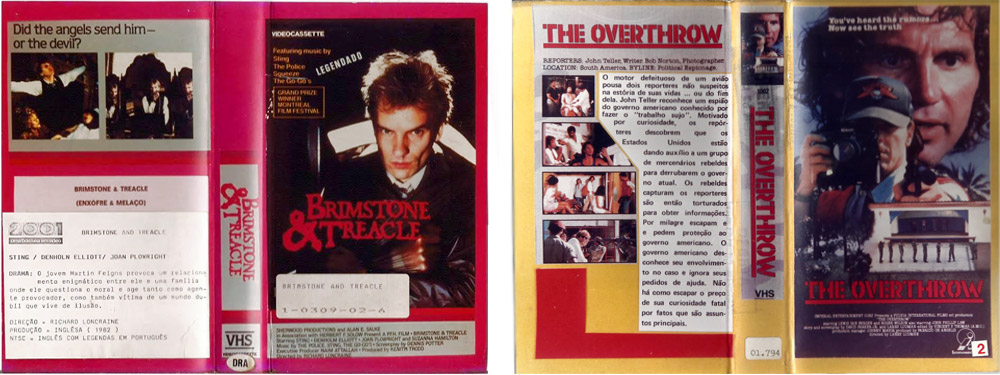

Computer-based piracy was originally a means of distributing, testing, and getting to grips with technologies amongst a small group of users. It was indeed not too dissimilar from the type of group activity that brought into existence the free software movement. It was a commonplace occurrence to supply your friends and colleagues with a copy of software. Clubs formed and began to learn the basics of computer programming by decoding software programmes to the great displeasure of the then infant IT industry, as attested by Bill Gates’ infamous letter of 1976 that The Pirate Book has exhumed and which denounces amateur IT practitioners for sharing the BASIC programme created by his fledgling company Altair. IT manufacturers made a concerted effort to shift the original meaning of the word hacker (which until that time had been associated with a positive form of DIY) that was then conflated with cracker which translates as “pirate.” The view underpinning this semantic shift was later adopted by the cultural industries with regards to P2P users, and is analysed by Vincent Mabillot. This privatisation of the code and the creation of software protection mechanisms led users to rebel by cracking digital locks and by fostering anti-corporate ideas in the name of free access. At a time when commercial software and IT net-works gained momentum and complexity, a more or less independently instituted division of labour emerged among specialised pirates who belonged to what is termed The Scene. The Scene is the source of most pirated content that is made publicly available and then disseminated via IRC, P2P, and other file sharing services used by the general public. The Scene comprises, amongst others, small autonomous groups of pirates who compete to be the first to secure and release the pirated version of digital content. The Pirate Book sheds light on the modus operandi and iconography of this Warez culture (the term designates the illicit activities of disseminating copyright protected digital content) from which the content consumed online in the most well connected countries originates and which is subsequently resold at heavily discounted prices at stalls across the globe.

TORRENT POISONING:

WHAT THE FUCK DO YOU THINK YOU’RE DOING?

In the context of this continual game of hide and seek, the cultural industries have proven to be surprisingly creative in the strategies they employ to combat piracy as substantiated by the documents on display in this book: from educational flyers to intimidation, from hologram stickers to game alterations, from false TV signal detectors (mysterious vans equipped with weird and wonderful antenna that are supposed to strike fear in the hearts of those who have not paid their TV licence) to show trials such as the 2009 high-profile case of the Swedish founders of the emblematic peer-to-peer platform, The Pirate Bay. Pirate or “privateer” tactics are even employed by certain corporations. These tactics include torrent poisoning which consists in sharing data that has been corrupted or files with misleading names on purpose. In this particular case, the reader is at liberty to copy the texts of this book and do with them as he/she pleases. The book’s authors (editors?) have opted for copyleft, a popular alternative to copyright. The term copyleft was brought into popular usage by Richard Stallman who founded the freeware movement and refers to an authorization to use, alter and share the work provided that the authorization itself remains untouched. Pirates’ challenging and transgression of the conventions of intellectual property have become a form of resistance to the ever increasing surveillance of users of digital technologies by corporate and state interests. In doing so, pirates have opened the way to new “perspectives of counter-societies that work along different lines.”

The Pirate Book makes its own particular contribution to this debate by painting a different picture, one embedded in the geographic realities of piracy, of these frequently scorned practices. In the same way that piracy itself is difficult to pinpoint, this book endeavours to capture the breadth of the phenomenon through images and accounts garnered online. It combines the global and the hyper local, states of being on and offline, anecdotes and immersion, poetic references, and technical decryption, thereby eschewing conventional categories used to classify publications. The Pirate Book is indeed neither an artist book, nor an academic dissertation, nor an archive, nor a forecast study. It is a blend of all of the latter and forms a prolific guide that can be read as much as it can be looked at. By focusing on situations, objects, documents, and individuals, this work enables us to envision the potential for future cross-purpose practices that could emerge in a networked society.

thepiratebook.net - 2015